The Coast Guard’s Efforts to Attain Mission Critical Ships Are Delayed and Over Budget

The U.S. Coast Guard plays a key role in national defense and security—patrolling areas like our ports and waterways, and operating in the Arctic and Antarctic. However, efforts to build and buy two types of ships that are critical to the Guard’s mission have long been delayed and run over their cost estimates.

Today’s WatchBlog post looks at our work on the Coast Guard’s efforts to replace aging ships with its new Offshore Patrol Cutters and Polar Security Cutters.

The Polar Star, an icebreaker that is nearly 50 years old

Image

Cutters: The cutting edge

The Coast Guard’s two highest priority acquisition programs are the Polar Security Cutter and the Offshore Patrol Cutter.

Polar Security Cutters. The Coast Guard’s heavy polar icebreakers are intended to ensure access to the Arctic and Antarctic—critical to protecting the U.S. economic and national security interests in the regions. But currently, the Coast Guard relies on the Polar Star, its only remaining heavy polar icebreaker, which has aging systems, resulting in some issues during deployment. For example, during the 2021–2022 mission, the Polar Star was at risk of colliding into another vessel after experiencing a propulsion control failure.

The Coast Guard has long planned to replace the Polar Star with three new ships called Polar Security Cutters. But, while the Coast Guard plans to start construction on these new ships in March 2024, it hasn’t fully developed the design for these ships. For example, icebreaking hulls require thick steel—up to twice as thick as a non-icebreaker. But the dense framing structure that is needed has been challenging to plan for and is not yet fully designed. Starting ship construction without a stable design is risky because it can lead to costly repairs and schedule delays.

Offshore Patrol Cutters. The Coast Guard currently has a fleet of aging Medium Endurance Cutters that help carry out a variety of missions, such as conducting patrols for homeland security, law enforcement, and search and rescue operations. But like the icebreakers, these patrol cutters have been in operation for decades. The oldest has been in service for 56 years. Maintaining and operating these ships is expensive. To replace them, the Coast Guard plans to acquire a fleet of 25 new Offshore Patrol Cutters from at least two different ship builders. These newest cutters are intended to deliver greater capability than the legacy ships that they will replace. For example, the cutters are expected to have increased endurance (time a ship can spend at sea), crew size, and operational range.

But, the Coast Guard doesn't have a plan to ensure that the Offshore Patrol Cutter's critical technology—a crane that deploys and retrieves the cutter's small boats used in operations—is fully developed before the lead ship is delivered. It has already encountered a number of obstacles that have prevented the crane from maturing. For instance, one challenge with the crane’s design is that the electrical cabinet that powers the crane was initially too big to fit inside the ship. As a result, one component of the cabinet was moved to the cutter’s exterior deck. Then, this component needed to be altered to ensure the electrical components could withstand extreme offshore weather and other conditions it might be exposed to on deck. This has led to multiple redesigns and delays. The Coast Guard also doesn’t have a plan to mature this technology for the next stage of ships recently awarded to a second shipbuilder prior to construction. Consequently, the Coast Guard risks the same types of development delays as experienced by the first shipbuilder.

Learn more about the challenges the Coast Guard has had with its Offshore Patrol Cutter efforts by listening to our podcast with GAO’s Marie Mak, an expert on Coast Guard acquisitions.

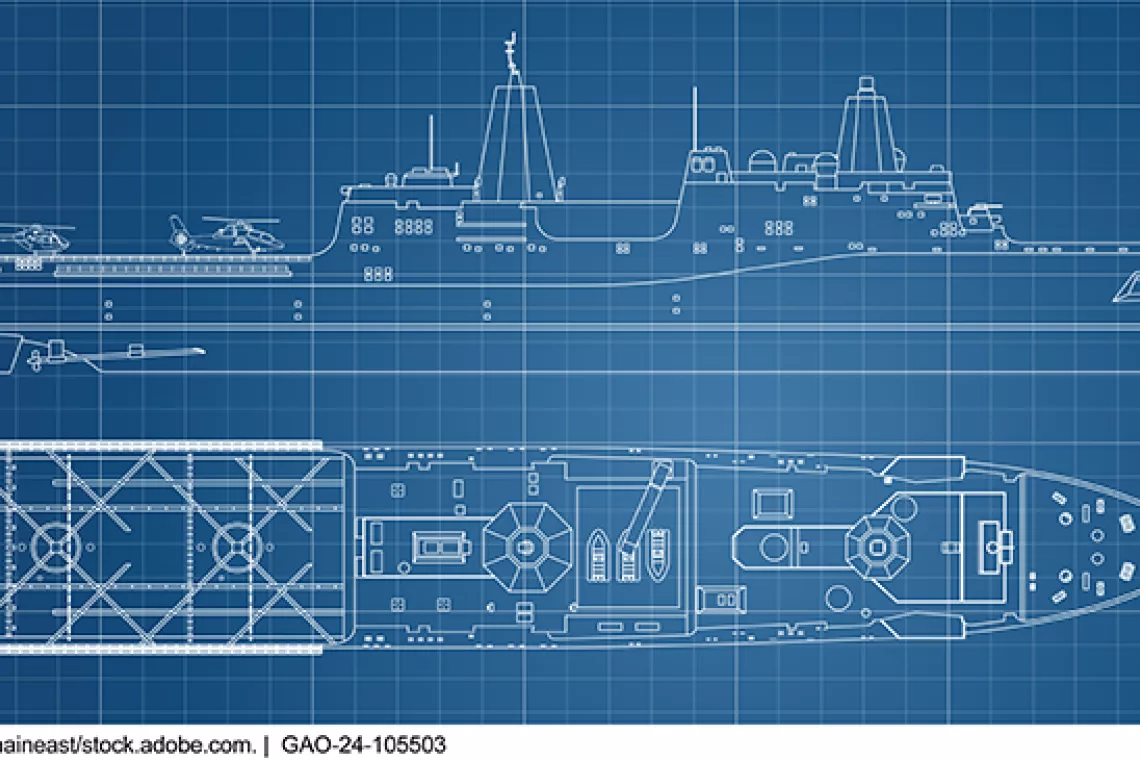

The Coast Guard’s Offshore Patrol Cutter and Polar Security Cutter

Image

What we can learn from the Coast Guard’s Cutters efforts

The Coast Guard is trying to design and build these two new cutters to deliver them quickly to its fleet. But, we found that efforts were stymied because the Coast Guard failed to obtain the necessary knowledge about the ships’ technology, design, and cost at key decision points before moving forward. These problems cascade through the Coast Guard’s shipbuilding portfolio, causing cost increases and schedule delays that end up putting more pressure on the aging legacy ships.

Moving forward without the necessary knowledge to develop the cutters will cost the Coast Guard more money and force the extended use of already aging ships. For example, in June, we reported that the Coast Guard plans to reduce the number of Offshore Patrol Cutters available for operation starting in 2024 due to delivery delays. So, the Coast Guard will likely need to further maintain and keep its existing, aging cutters in service longer at a projected cost of $250 million. Similarly, it plans to invest $75 million to extend the service life of the Polar Star, which is almost 50 years old, until the delayed Polar Security Cutters are operational.

How can the Coast Guard improve its process for designing and building ships? We recommended that the Coast Guard prioritize full development of the Offshore Patrol Cutter’s crane before key decision points. We also recommended that the Department of Homeland Security ensure that the Coast Guard adequately develop the design of the Polar Security Cutter before authorizing the Coast Guard to build it.

- Comments on GAO’s Watching? Contact blog@gao.gov.