Embassy Management: Increasing Costs and Natural Hazards Threaten State’s Efforts

Highlights

The Big Picture

The State Department’s Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations (State) provides U.S. diplomatic facilities around the world. State is responsible for managing some 9,000 owned and 16,000 leased assets, supporting some 90,000 U.S. government personnel in about 290 locations worldwide. These assets represent a wide array of facilities including its embassy and consulate compounds (hereafter “embassies”).

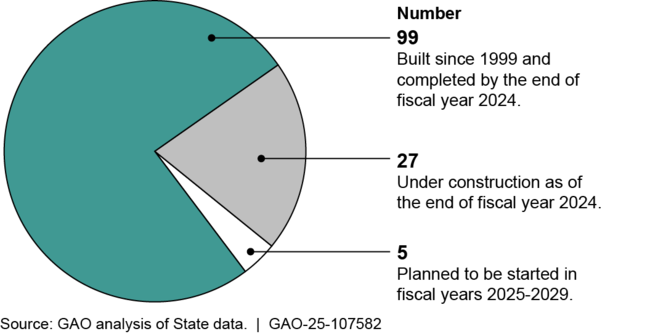

Since the 1998 bombings of two U.S. embassies in East Africa, State has built 99 embassies under its Capital Security Construction Program (CSCP), while prioritizing security, at a program cost of about $40 billion through fiscal year 2024. Since 2015, State has provided about $2 billion in annual funding for the CSCP for new embassy construction. Several embassies have cost State about $1 billion each to build, including in Kabul, Afghanistan; Mexico City, Mexico; and Beirut, Lebanon.

State also provides about $500 million annually for maintenance of its embassies, including repairs and major facility rehabilitations. Embassy resilience to hazards is increasingly important. Many cities hosting U.S. embassies are threatened by a variety of natural hazards (e.g. earthquakes) and climate change related hazards (e.g. coastal flooding).

What GAO’s Work Shows

Information Sharing Highlights How Inflation Increased Cost and Slowed Pace of Construction Program

We have regularly monitored State’s embassy construction program, implemented in the aftermath of the 1998 embassy bombings. In 2018, we reported that State would not reach its stated construction goals, in part because funding for new construction has not kept pace with inflation. For completed embassies, later additions such as housing for U.S. Marine security guards have increased program costs and slowed the pace of construction.

U.S. Embassy Construction: Fiscal Years 1999-2024

Note: The figure above excludes new embassies, consulates and facilities not built with Capital Security Construction Program funds, such as the embassy in London, United Kingdom, and the American Institute in Taiwan, Taipei, Taiwan, among others. The figure also excludes newly acquired buildings and new office buildings on existing compounds.

We recommended that State determine the estimated effects of increased costs on planned embassy construction capacity and time frames and share this information with congressional stakeholders. State has addressed this recommendation. In January 2020, State reported that replacing all its remaining embassies (estimated at 160 at the time) would cost over $58 billion in 2020 dollars and construction would take 25 to 30 years to complete.

Since that time, inflation has continued to erode State’s purchasing power. In its 2025 budget request, State estimates that since 2015, the capital construction program will have lost $1.1 billion in purchasing power. Because State is now providing information on projected pace of construction and the estimated effects of inflation, stakeholders can make more informed budget decisions regarding State’s construction resources and capacity.

More Planning Could Help State Better Understand Deferred Maintenance Needs and Staff Skills

In 2021, we reported State had difficulties in maintaining the condition of its embassies. We found that more than one-quarter of State’s assets were in poor condition according to State’s standards. Further, 20 percent (almost 400) of the assets that State identified as critical to its mission were in poor condition. State had set a single acceptable condition standard of “fair” for all assets and did not consider whether some assets were more critical when estimating its $3 billion deferred maintenance backlog, as last reported in 2023.

In light of these findings, we recommended that State reassess its acceptable condition standard for all assets and develop a plan to address its deferred maintenance backlog. State has since determined that assets critical to its mission, such as embassy buildings and communications towers, warrant a higher acceptable condition standard, while less critical or more easily replaceable facilities can warrant a lower acceptable condition standard. Because of this and other changes to its methodology for determining deferred maintenance, State expects future estimates of deferred maintenance to be lower than last reported.

While State has addressed our recommendation to reassess its acceptable condition standard for its assets, it still faces a substantial backlog, which it has not yet developed a plan to address. Developing and sharing a plan to address this backlog would help decision makers, including Congress, better evaluate State’s budget requests and understand how funding levels affect backlog reduction.

In addition, we reported in 2023 that State has faced challenges hiring American and locally employed facilities staff to maintain U.S. embassies, and that State did not have inventories of the technical skills needed.

Examples of Locally Employed Maintenance Staff At Work

State has not yet implemented our recommendation to develop guidance for embassies to create and maintain such inventories for locally employed staff. Doing so could improve State’s workforce planning.

Aligning Plans with Resources Will Help State Better Understand What Its Natural Hazard Resilience Program Can Accomplish

In 2022, we assessed State’s efforts to address the threats to its embassies from natural hazards and weather events, which are becoming increasingly more frequent and severe. We reported that State identified and assessed the risks to its facilities presented by natural and climate hazards and the potential effects to each embassy’s mission should a natural disaster occur. As part of our review, we prepared an interactive map that shows the levels of risk embassy facilities face from the eight natural hazards for which State had collected data.

Related to State’s risk assessments, in 2023, we reported that State’s Climate Security and Resilience (CS&R) program—responsible for helping embassies plan, fund, and implement facility resilience projects—had limited staffing to fully enact plans outlined in State’s 2021 Climate Adaptation and Resilience Plan. We recommended that State revisit the CS&R program plans, goals, and timeframes, and adjust them as appropriate. While State has increased its CS&R staff and is planning to add more, as of August 2024, it did not have sufficient staff to fully implement its resilience program plans nor had it revisited these plans. By aligning CS&R program plans with its available staffing, State can more clearly establish how the CS&R program can support State’s embassy climate resilience goals.

Challenges and Opportunities

U.S. government staff abroad and their families depend on safe, secure, and functional diplomatic facilities. State’s embassy management efforts are costly and time-intensive and these investments are affected by inflation, deferred maintenance, and the risk of natural hazards. To strengthen its efforts moving forward, State should implement open GAO recommendations. In addition, policymakers play an important oversight role as they continue to examine and consider State’s priorities for embassy construction, maintenance, and resilience, and how best to use available funding to protect past and future investments in U.S. embassies.

For more information, contact Tatiana Winger at (617) 788-0572 or wingert@gao.gov or Brian Bothwell at (213) 830-1160 or bothwellb@gao.gov.