Immigration: Actions Needed to Strengthen USCIS's Oversight and Data Quality of Credible and Reasonable Fear Screenings

Fast Facts

Noncitizens apprehended by DHS may be removed from the U.S. without an immigration hearing unless they express an intent to apply for asylum or a fear of persecution or torture.

Such “fear claims”—108,780 in FY2018—are referred to DHS’s immigration services agency, which determines whether there is a credible fear of persecution or torture, also known as a “positive determination.”

The agency screens family members individually but certain members can share positive determinations, or the agency may decide to keep them together. But, it doesn’t record complete data on all such results. We recommended it do so to better report on screenings.

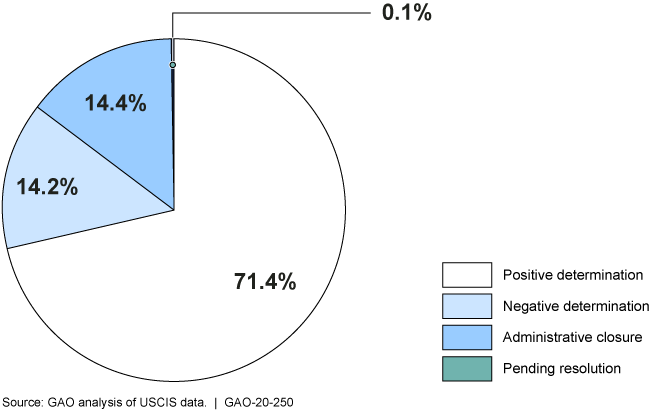

Outcomes of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Credible and Reasonable Fear Screenings, Fiscal Year 2014 through the First Two Quarters of 2019

Pie chart showing most outcomes are positive determinations

Highlights

What GAO Found

Data from the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and Department of Justice's Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) indicate that their credible and reasonable fear caseloads generally increased from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2018.

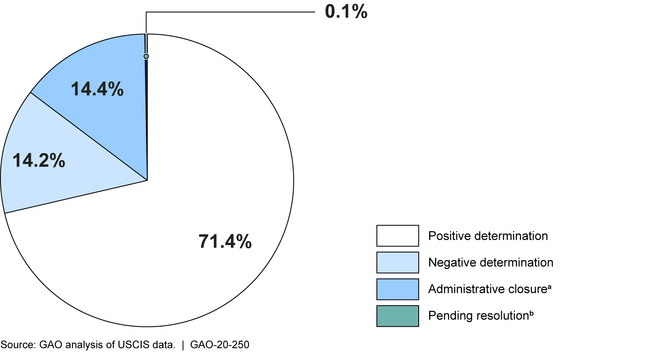

USCIS's caseloads nearly doubled during this timeframe—from about 56,000 to almost 109,000 referrals for credible and reasonable fear screenings. Further, the credible fear caseload was larger in the first two quarters of fiscal year 2019 alone than in each of fiscal years 2014 and 2015. Referrals to USCIS for reasonable fear screenings also increased from fiscal years 2014 through 2018. USCIS asylum officers made positive determinations in 71 percent of all credible and reasonable fear screenings between fiscal years 2014 and the first two quarters of fiscal year 2019. The outcomes of the remaining screenings were generally split evenly (14 percent each) between negative determinations or administrative closures (such as if the applicant was unable to communicate).

EOIR's caseload for immigration judge reviews of USCIS's negative credible and reasonable fear determinations also increased between fiscal year 2014 and fiscal year 2018. EOIR's immigration judges reviewed about 55,000 cases from fiscal year 2014 through the third quarter of 2019 (the most recent data available), and judges upheld USCIS's negative determinations in about three-quarters of all reviews.

Outcomes of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Credible and Reasonable Fear Screenings, Fiscal Years 2014 through the First Two Quarters of Fiscal Year 2019

aAccording to USCIS, administrative closures occur when the asylum officer conducting the screening closes the case without a determination for reasons such as death, presence in state or federal custody, inability to communicate, or other reasons.

bUSCIS cases occurred from October 1, 2013 through March 30, 2019 and their status was as of July 22, 2019. Cases that remained in progress as of July 22, 2019 were “pending resolution.”

USCIS has developed various policies and procedures for overseeing credible and reasonable fear screenings in accordance with the regulations governing those screenings, such as interview requirements and mandatory supervisory review. USCIS provides basic training for new asylum officers and other training at individual asylum offices that includes credible and reasonable fear. The training at asylum offices includes on-the-job training for officers newly-assigned to credible and reasonable fear cases and ongoing weekly training for incumbent officers—some of which includes credible and reasonable fear. However, USCIS asylum offices do not all provide additional pre-departure training before officers begin screening families in person at DHS's family residential centers. Asylum Division officials told GAO that additional training for asylum officers before they begin screening such cases is important—in particular, credible fear screenings at these facilities represent about one-third of USCIS's caseload. Almost all USCIS asylum offices send officers to the family residential centers, including those offices with small fear caseloads at the local level. Some asylum offices provide pre-departure training to officers being sent to screen families, but such training is inconsistent across offices. By comparison, officials from the Chicago and New York offices stated they do not provide formal pre-departure training, but rather direct or recommend that officers review Asylum Division guidance and procedures on family processing independently before they travel. Officials from two other offices stated they rely on the training asylum officers may receive throughout the year related to credible and reasonable fear, which can vary. Providing pre-departure training, in addition to USCIS's basic training for new asylum officers, would help USCIS ensure that officers from all asylum offices are conducting efficient and effective fear screenings of families.

Further, consistent with regulation, USCIS policy is to include any dependents on a principal applicant's credible fear determination if the principal applicant receives a positive determination, resulting in the principal and any dependents being placed into full removal proceedings with an opportunity to apply for various forms of relief or protection, including asylum. For example, a parent as a principal applicant may receive a negative determination, but his or her child may receive a separate positive determination. In the interest of family unity, USCIS may use discretion to place both the parent and child into full removal proceedings rather than the parent being expeditiously ordered removed in accordance with the expedited removal process. However, USCIS's case management system does not allow officers to record whether an individual receives a determination on his or her case as a principal applicant, dependent, or in the interest of family unity. Without complete data on all such outcomes, USCIS is not well-positioned to report on the scope of either the agency's policy for family members who are treated as dependents, pursuant to regulation, or USCIS's use of discretion in the interest of family unity.

USCIS and EOIR have processes for managing their respective credible and reasonable fear workloads. For example, USCIS uses national- and local-level staffing models to inform staffing allocation decisions. USCIS also sets and monitors timeliness goals for completing credible and reasonable fear cases. Although USCIS monitors overall processing times, it does not collect comprehensive data on some types of case delays, which officers told us can occur on a regular basis. Asylum officers whom GAO interviewed stated that certain delays could affect the number of credible or reasonable fear cases they can complete each day. Collecting and analyzing additional information on case delays would better position USCIS to mitigate the reasons for the delays and improve efficiency. EOIR has developed processes for immigration courts and judges to help manage its workload that include performance measures with timeliness goals for credible and reasonable fear reviews. EOIR data indicate that about 30 percent of credible and reasonable fear reviews are not completed within the required timeframes. EOIR officials said they plan to implement an automated tool in early 2020 to monitor court performance, including the credible and reasonable fear performance goals. Because implementation of the automated tool is planned for early 2020, it is too soon to know if EOIR will use the tool to monitor adherence to the required credible and reasonable fear review time frames or if it will help EOIR understand reasons for case delays.

Why GAO Did This Study

Individuals apprehended by DHS and placed into expedited immigration proceedings are to be removed from the country without a hearing in immigration court unless they express an intention to apply for asylum, or a fear of persecution, torture, or return to their country. Those with such “fear claims” are referred to USCIS for a credible fear screening. Individuals who have certain criminal convictions or who have a reinstated order of removal and claim fear are referred for a reasonable fear screening. Those with negative outcomes can request a review by EOIR's immigration judges. GAO was asked to review USCIS's and EOIR's processes for fear screenings.

This report examines (1) USCIS and EOIR data on fear screenings, (2) USCIS policies and procedures for overseeing fear screenings, and (3) USCIS and EOIR processes for workload management. GAO analyzed USCIS and EOIR data from fiscal years 2014 through mid-2019; interviewed relevant headquarters and field officials; and observed fear screenings in California, Texas, and Virginia, where most screenings occur.

Recommendations

GAO is making four recommendations, including that USCIS provide additional pre-departure training to USCIS asylum officers before they begin screening families, systematically record case outcomes of family members, and collect and analyze information on case delays. DHS concurred with GAO's recommendations.

Recommendations for Executive Action

| Agency Affected | Recommendation | Status |

|---|---|---|

| United States Citizenship and Immigration Services | The Director of USCIS should ensure that, in addition to USCIS's basic asylum officer training, all asylum offices provide pre-departure training on the credible and reasonable fear processes before their officers begin screening cases at the family residential centers. (Recommendation 1) |

We reported that all new asylum officers received basic training on the credible and reasonable fear screening process, and may have received on-the-job training in their home asylum offices. However, not all offices provided additional pre-departure training to asylum officers before they began screening cases for family units at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement family residential centers. Arlington and Houston asylum office officials stated that inconsistent asylum officer training on credible and reasonable fear cases negatively impact efficiency at the family residential centers. As a result, we recommended that all asylum offices provide pre-departure training on the credible and reasonable fear processes before their officers begin screening cases at the family residential centers. In response, the Asylum Division developed a standardized training focused on handling and assessing fear claims raised by family units. This training, tailored to officers' level of experience, is required before they can conduct credible and reasonable fear interviews of family units, including those interviewed at family residential centers. The online training was released to officers on July 29, 2021. Providing pre-departure training, in addition to USCIS's basic training for new asylum officers, should help U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services ensure that officers from all asylum offices are conducting efficient and effective fear screenings of families.

|

| United States Citizenship and Immigration Services | The Director of USCIS should develop and implement more specific guidance on requirements for documenting results of Asylum Division periodic quality assurance reviews. (Recommendation 2) |

In June 2020, USCIS developed a template for documenting the findings of their periodic quality assurance review reports. In September 2020, USCIS officials stated that this template would be used for future periodic reviews. Incorporating this template into future reviews of asylum, credible and reasonable fear, and other case decisions will ensure that the outcomes of periodic quality assurance reviews involving similar case types are documented in a consistent manner. This consistent documentation will assist the agency in better tracking trends across the asylum offices.

|

| United States Citizenship and Immigration Services | The Director of USCIS should ensure asylum officers systematically record in USCIS's automated case management system if individuals receive credible fear determinations as principal applicants, dependents, or in the interest of family unity, pursuant to regulation or USCIS policy. (Recommendation 3) |

In February 2020, we reported that U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services' (USCIS) asylum officers are to record individual credible fear screening outcomes for all family members in USCIS's automated case management system. However, Asylum Division officials said their system did not allow asylum officers to record whether an individual receives a credible fear determination as a principal applicant, dependent, or in the interest of family unity. Specifically, we reported that the system did not allow officers to record whether an applicant's determination stems from his or her own case, or from a family member's case. Therefore, we recommended that USCIS ensure asylum officers systematically record in USCIS's automated case management system if individuals receive credible fear determinations as principal applicants, dependents, or in the interest of family unity, pursuant to regulation or USCIS policy. In response, USCIS created a new field in its case management system requiring officers to enter whether an individual received a positive credible fear determination as a principal, dependent, or in the interest of family unity. USCIS implemented this new field nationwide on January 7, 2021. Recording such data in its case management system should help ensure that USCIS is well-positioned to report on all outcomes of credible fear screenings at family residential centers.

|

| United States Citizenship and Immigration Services | The Director of USCIS should collect and analyze additional information on case delays, including specific reasons for delays and how long they last, that asylum officers may face when screening credible and reasonable fear cases. (Recommendation 4) |

In February 2020, we found that USCIS's Asylum Division monitored overall processing times for credible and reasonable fear cases, but did not collect comprehensive data in its case management system on some types of case delays. In particular, we found that USCIS's case management system did not track specific logistical reasons for certain delays in credible and reasonable fear cases, which affected the number of cases an officer can complete in a day. Therefore, we recommended that USCIS collect and analyze additional information in its automated case management system on case delays that asylum officers may face-and how long they last- when screening credible and reasonable fear cases. In response, as of October 2021, the Asylum Division incorporated additional case delay reasons into its case management system such as a lack of phone lines, interview space, or interpreters. In addition, as of February 2021, the Asylum Division created a new feature in its case management system and required officers to record the total length of any delays in case processing, if applicable, beyond the standard 14 calendar days for both reasonable and credible fear cases. Further, the Asylum Division implemented a new data dashboard to report reasons for case delays and allow USCIS to better analyze the new data collected. Collecting and analyzing such data should help USCIS better identify case delay reasons relevant in the current environment for officers conducting credible and reasonable fear screenings and better position USCIS to mitigate the reasons for the delays and improve efficiency in case processing.

|