Information Technology: DHS Directives Have Strengthened Federal Cybersecurity, but Improvements Are Needed

Fast Facts

The Department of Homeland Security issues mandatory cybersecurity directives for most federal agencies. For example, one directive requires agencies to better secure their websites and email systems. If the actions specified in these directives are not addressed, agency systems can remain at risk.

We found that these directives have often been effective in strengthening federal cybersecurity. However, agencies and DHS didn’t always complete the directives’ actions on time. DHS also did not consistently ensure that agencies fully complied with the directives. We recommended that DHS address these issues.

Homeland Security building and sign

Highlights

What GAO Found

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has established a five-step process for developing and overseeing the implementation of binding operational directives, as authorized by the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA). The process includes DHS coordinating with stakeholders early in the directives' development process and validating agencies' actions on the directives. However, in implementing the process, DHS did not coordinate with stakeholders early in the process and did not consistently validate agencies' self-reported actions. In addition to being a required step in the directives process, FISMA requires DHS to coordinate with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to ensure that the directives do not conflict with existing NIST guidance for federal agencies. However, NIST officials told GAO that DHS often did not reach out to NIST on directives until 1 to 2 weeks before the directives were to be issued, and then did not always incorporate the NIST technical comments. More recently, DHS and NIST have started regular coordination meetings to discuss directive-related issues earlier in the process. Regarding validation of agency actions, DHS has done so for selected directives, but not for others. DHS is not well-positioned to validate all directives because it lacks a risk-based approach as well as a strategy to check selected agency-reported actions to validate their completion.

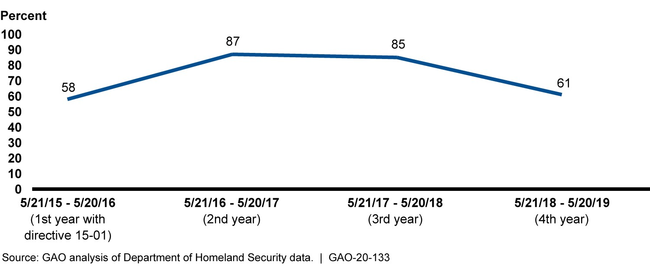

Directives' implementation often has been effective in strengthening federal cybersecurity. For example, a 2015 directive on critical vulnerability mitigation required agencies to address critical vulnerabilities discovered by DHS cyber scans of agencies' internet-accessible systems within 30 days. This was a new requirement for federal agencies. While agencies did not always meet the 30-day requirement, their mitigations were validated by DHS and reached 87 percent compliance by 2017 (see fig. 1). DHS officials attributed the recent decline in percentage completion to a 35-day partial government shutdown in late 2018/early 2019. Nevertheless, for the 4-year period shown in the figure below, agencies mitigated within 30 days about 2,500 of the 3,600 vulnerabilities identified.

Figure 1: Critical Vulnerabilities Mitigated within 30 days, May 21, 2015 through May 20, 2019

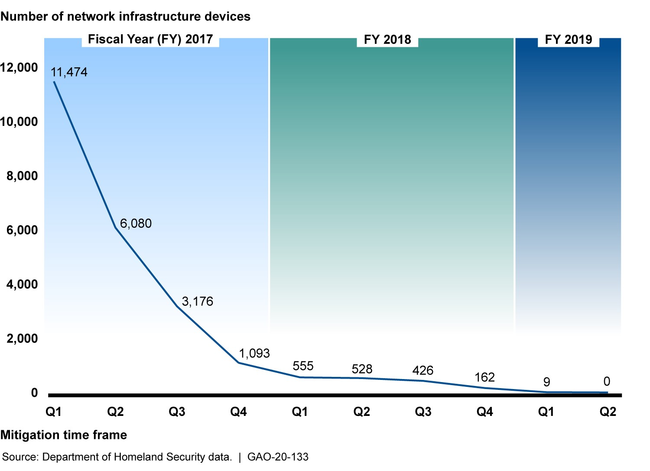

Agencies also made reported improvements in securing or replacing vulnerable network infrastructure devices. Specifically, a 2016 directive on the Threat to Network Infrastructure Devices addressed, among other things, several urgent vulnerabilities in the targeting of firewalls across federal networks and provided technical mitigation solutions. As shown in figure 2, in response to the directive, agencies reported progress in mitigating risks to more than 11,000 devices as of October 2018.

Figure 2: Federal Civilian Agency Vulnerable Network Infrastructure Devices That Had Not Been Mitigated, September 2016 through January 2019

Another key DHS directive is Securing High Value Assets, an initiative to protect the government's most critical information and system assets. According to this directive, DHS is to lead in-depth assessments of federal agencies' most essential identified high value assets. However, an important performance metric for addressing vulnerabilities identified by these assessments does not account for agencies submitting remediation plans in cases where weaknesses cannot be fully addressed within 30 days. Further, DHS only completed about half of the required assessments for the most recent 2 years (61 of 142 for fiscal year 2018, and 73 of 142 required assessments for fiscal year 2019 (see fig. 3)). In addition, DHS does not plan to finalize guidance to agencies and third parties, such as contractors or agency independent assessors, for conducting reviews of additional high value assets that are considered significant, but are not included in DHS's current review, until the end of fiscal year 2020. Given these shortcomings, DHS is now reassessing key aspects of the program. However, it does not have a schedule or plan for completing this reassessment, or to address outstanding issues on completing required assessments, identifying needed resources, and finalizing guidance to agencies and third parties.

Figure 3: Department of Homeland Security Assessments of Agency High Value Assets, Fiscal Years (FY) 2018 through 2019

Why GAO Did This Study

DHS plays a key role in federal cybersecurity. FISMA authorized DHS, in consultation with the Office of Management and Budget, to develop and oversee the implementation of compulsory directives—referred to as binding operational directives—covering executive branch civilian agencies. These directives require agencies to safeguard federal information and information systems from a known or reasonably suspected information security threat, vulnerability, or risk. Since 2015, DHS has issued eight directives that instructed agencies to, among other things, (1) mitigate critical vulnerabilities discovered by DHS through its scanning of agencies' internet-accessible systems; (2) address urgent vulnerabilities in network infrastructure devices identified by DHS; and (3) better secure the government's highest value and most critical information and system assets.

GAO was requested to evaluate DHS's binding operational directives. This report addresses (1) DHS's process for developing and overseeing the implementation of binding operational directives and (2) the effectiveness of the directives, including agencies' implementation of the directive requirements. GAO selected for review the five directives that were in effect as of December 2018, and randomly selected for further in-depth review a sample of 12 agencies from the executive branch civilian agencies to which the directives apply.

In addition, GAO reviewed DHS policies and processes related to the directives and assessed them against FISMA and Office of Management and Budget requirements; administered a data collection instrument to selected federal agencies; compared the agencies' responses and supporting documentation to the requirements outlined in the five directives; and collected and analyzed DHS's government-wide scanning data on government-wide implementation of the directives. GAO also interviewed DHS and selected agency officials.

Recommendations

GAO is making four recommendations to DHS: (1) determine when in the directive development process—for example, during early development and at directive approval—coordination with relevant stakeholders, including NIST, should occur; (2) develop a strategy for when and how to independently validate selected agencies' self-reported actions on meeting directive requirements, where feasible, using a risk-based approach; (3) ensure that the directive performance metric for addressing vulnerabilities identified in high value asset assessments aligns with the process DHS has established; and (4) develop a schedule and plan for completing the high value asset program reassessment and addressing the outstanding issues on completing the required assessments, identifying needed resources, and finalizing guidance to agencies and third parties. DHS concurred with GAO's recommendations and outlined steps and associated timelines that it planned to take to address the recommendations.

Recommendations for Executive Action

| Agency Affected | Recommendation | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Office of the Secretary for DHS | The Secretary of Homeland Security should determine when in the directive development process—for example, during early development and at directive approval—coordination with relevant stakeholders, including NIST and GSA, should occur. (Recommendation 1) |

DHS finalized its draft directive development process on March 12, 2020, to include steps to coordinate with relevant stakeholders at specific phases in the directive development process. Specifically, the document states that DHS's Cybersecurity Division Leadership is to coordinate with Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and NIST leadership during the directive initiation and development phase. According to the document, during the "Develop and Approve" phase of the directive development process, external partners such as GSA, NIST, and OMB should be notified of the development of the directive. By taking this step, DHS will ensure proper coordination and address possible concerns early on and throughout the directive's development.

|

| Office of the Secretary for DHS | The Secretary of Homeland Security should develop a strategy to independently validate selected agencies' self-reported actions on meeting binding operational directive requirements, where feasible, using a risk-based approach. (Recommendation 2) |

In April 2021, the Department of Homeland Security's Cyber and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) updated its CISA Cyber Directives Process document to include a risk-based approach to validating selected agency actions on meeting binding operational directive requirements, as appropriate. CISA's process notes that determining the data elements for tracking and validating agency compliance with the directive will occur early in the development process.

|

| Office of the Secretary for DHS | The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the binding operational directive performance metric for addressing vulnerabilities identified by high value asset assessments aligns with the process DHS has established. (Recommendation 3) |

In a July 2020 update to its Agency Priority Goals, DHS stated that the department had updated its performance goals and metrics to more closely align with the high value asset assessments process. Specifically, in its recent Agency Priority Goals update to performance.gov, DHS adjusted its high value asset assessment metric to differentiate between structural vulnerabilities, which may take a long time to address, and configuration-based vulnerabilities which can be addressed more quickly. For example, in its July 2020 report for OMB's performance.gov web site, it was noted that by September 30, 2021, 75% of critical and high configuration-based vulnerabilities identified through high value asset assessments are to be mitigated within 30 days. This aligns with the requirement to address critical and high vulnerabilities within 30 days in the directive. While the department noted in its report that it continues to track the percent of structural deficiencies remediated within 30 days as a key indicator, it is not using it as a primary performance metric. Separating the two types of vulnerabilities will help DHS better demonstrate agencies progress in addressing high value asset vulnerabilities.

|

| Office of the Secretary for DHS |

Priority Rec.

The Secretary of Homeland Security should develop a schedule and plan for completing the high value asset program reassessment and addressing the outstanding issues on completing the required high value asset assessments, identifying needed resources, and finalizing guidance for Tier 2 and 3 HVA systems. (Recommendation 4) |

In March 2021, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued supplemental guidance on its high value assessment (HVA) program and has taken other actions that address outstanding issues associated with the HVA assessments. Specifically, the guidance consolidated multiple assessments into a single HVA assessment to reduce resource needs and includes guidance for non-Tier 1 HVA systems (previously Tier 2 and 3). Additionally, DHS officials noted that the department increased its staffing levels to support completing required Tier 1 HVA assessments on an ongoing basis. They noted that changes to the assessments and increased staffing should allow them to complete required Tier 1 assessments on a three year rolling basis. Further, DHS officials noted that DHS has scheduled regular training for HVA assessors (for non-Tier 1 HVAs) in fiscal years 2021 and 2022 and plans to continue training in fiscal year 2023. By taking these actions, agencies may likely reduce facing prolonged cybersecurity risks.

|