U.S. Department of Agriculture—Application of Recording Statute, Bona Fide Needs Statute, and Antideficiency Act to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Benefits

Highlights

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) administers the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides monthly benefits to low-income households to purchase food. SNAP is an appropriated entitlement, with benefits generally funded by a one-year appropriation provided by annual appropriations acts. Prior to September 19, 2023, USDA recorded daily obligations for SNAP in an amount equal to household benefits issued. On September 19, 2023, USDA changed this practice. On that date, USDA obligated its fiscal year (FY) 2023 one-year appropriation for FY 2024 SNAP benefits that would be issued to households during the month of October 2023. Here, we consider whether USDA's recording practices for SNAP in FY 2023 were consistent with the recording statute, the bona fide needs statute, and the Antideficiency Act.

We conclude that both practices violated the recording statute. The point of obligation for SNAP benefits is when appropriations for such payments have been enacted and are available for obligation, not when USDA takes action as part of the process to pay benefits. In addition, the proper amount to record was USDA's best estimate of the SNAP benefits due in FY 2023, not the amount of benefits issued each day or benefits due in FY 2024. We also conclude that USDA's change in practice violated the bona fide needs statute when it used its FY 2023 one-year SNAP appropriation to pay for FY 2024 SNAP benefits. However, USDA complied with the bona fide needs statute with respect to its previous practice of recording obligations for SNAP benefits on a daily basis because the agency properly used its FY 2023 appropriation to pay for FY 2023 benefits. Finally, because USDA's FY 2023 one-year SNAP appropriation was not available to pay for FY 2024 benefits, USDA should adjust its accounts and charge those benefit amounts to appropriations available for obligation in FY 2024. If USDA lacks sufficient funds in the relevant appropriations, it must report an Antideficiency Act violation.

Decision

Matter of: U.S. Department of Agriculture—Application of Recording Statute, Bona Fide Needs Statute, and Antideficiency Act to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Benefits

File: B-336036

Date: February 12, 2025

DIGEST

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) administers the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides monthly benefits to low-income households to purchase food. SNAP is an appropriated entitlement, with benefits generally funded by a one-year appropriation provided by annual appropriations acts. Prior to September 19, 2023, USDA recorded daily obligations for SNAP in an amount equal to household benefits issued. On September 19, 2023, USDA changed this practice. On that date, USDA obligated its fiscal year (FY) 2023 one-year appropriation for FY 2024 SNAP benefits that would be issued to households during the month of October 2023. Here, we consider whether USDA's recording practices for SNAP in FY 2023 were consistent with the recording statute, the bona fide needs statute, and the Antideficiency Act.

We conclude that both practices violated the recording statute. The point of obligation for SNAP benefits is when appropriations for such payments have been enacted and are available for obligation, not when USDA takes action as part of the process to pay benefits. In addition, the proper amount to record was USDA's best estimate of the SNAP benefits due in FY 2023, not the amount of benefits issued each day or benefits due in FY 2024. We also conclude that USDA's change in practice violated the bona fide needs statute when it used its FY 2023 one-year SNAP appropriation to pay for FY 2024 SNAP benefits. However, USDA complied with the bona fide needs statute with respect to its previous practice of recording obligations for SNAP benefits on a daily basis because the agency properly used its FY 2023 appropriation to pay for FY 2023 benefits. Finally, because USDA's FY 2023 one-year SNAP appropriation was not available to pay for FY 2024 benefits, USDA should adjust its accounts and charge those benefit amounts to appropriations available for obligation in FY 2024. If USDA lacks sufficient funds in the relevant appropriations, it must report an Antideficiency Act violation.

DECISION

This responds to a request from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Office of Inspector General (OIG) on whether USDA's September 2023 change in practice for recording obligations for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits is consistent with the recording statute, the bona fide needs statute, and the Antideficiency Act.[1] The request stemmed from USDA OIG's audit of USDA's consolidated financial statements for fiscal years (FY) 2022 and 2023.[2] As explained below, we conclude that USDA violated the recording statute with respect to both its original and new recording practices. In addition, we conclude that while USDA's original practice for recording obligations during FY 2023 was consistent with the bona fide needs statute, USDA violated the statute when it used its FY 2023 appropriation to pay for FY 2024 benefits. Given the bona fide needs statute violation, USDA should adjust its accounts, and if it lacks sufficient funds in the relevant appropriations, it must report an Antideficiency Act violation.In accordance with our regular practice, we contacted USDA to seek factual information and its legal views on this matter.[3] USDA responded with its explanation of the pertinent facts and legal analysis.[4] We also requested and received the views of the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB).[5]

BACKGROUND

SNAP

SNAP is authorized by the Food and Nutrition Act of 2008, as amended (Food and Nutrition Act),[6] and provides monthly benefits to 42 million people to purchase food.[7] SNAP is jointly administered by USDA and the states. USDA pays the full cost of SNAP benefits (using the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond (Federal Reserve Bank) to make funds available), promulgates program regulations, and ensures state compliance with program rules. States are responsible for determining applicant eligibility, calculating the amount of their benefits, and issuing the benefits on Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards.[8]

Prior to issuing benefits, USDA sends a letter to the Federal Reserve Bank stating the maximum amount of funds available to states for the period in question.[9] Each day, USDA receives a file from the Federal Reserve Bank consolidating issuance data from the states.[10] USDA certifies the payments are proper, and the Federal Reserve Bank makes funds available to the states via individual letters of credit.[11] Benefits are issued to participants on EBT cards.[12]

SNAP benefits are primarily funded with one-year appropriations provided in annual appropriations acts.[13] These acts also generally provide a much smaller amount of three-year funds ($3 billion per year) (SNAP contingency fund) that is kept in reserve and is to be used only at such times as is necessary to carry out program operations.[14]

USDA Recording Practices

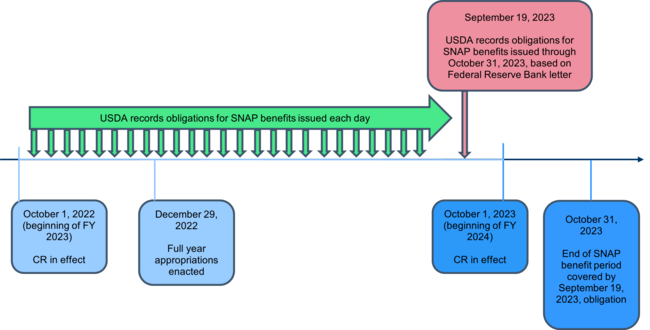

Prior to September 19, 2023, USDA recorded obligations each day in the amount of SNAP benefits issued to households that day.[15] USDA relied on Food and Nutrition Service Interface Inquiries to record these obligations.[16]

On September 19, 2023, USDA changed its practice and recorded obligations against its FY 2023 one-year appropriation for SNAP benefits that would be issued to households through October 31, 2023, in other words, through the first month of FY 2024.[17] USDA treated a September 19, 2023, letter to the Federal Reserve Bank as the point of obligation and recorded obligations based on the letter.[18] The letter informed the Bank of the maximum amount of funds available to states for SNAP benefits through October 31, 2023, along with the estimated value of SNAP benefits to be issued to each state during the period.[19] Specifically, the letter states, in relevant part:

Attached is a list of the estimated dollar value of SNAP benefits to be issued to each state, within the above-referenced funding limitation, for which the Food and Nutrition Service has incurred a legal liability in accordance with approved States Plans of Operation. Pursuant to 31 U.S.C. § 1501(a)(5)(A), that amount will be recorded as an obligation as of today's date.[20]

DISCUSSION

At issue here is whether USDA's recording practices with respect to SNAP benefits comply with the recording statute, the bona fide needs statute, and the Antideficiency Act. In particular: (1) when did USDA incur obligations for FY 2023 and October 2023 (FY 2024) SNAP benefits; (2) what amount should have been recorded for those obligations; and (3) whether those obligations and the corresponding expenditures comply with the bona fide needs statute.

Recording Statute

(1) Point of Obligation

An obligation occurs when an agency incurs a legal liability or a legal duty that could mature into a legal liability by virtue of actions beyond the control of the agency. B‑333150, Apr. 8, 2024; B‑300480, Apr. 9, 2003. The recording statute, 31 U.S.C. § 1501, requires that an agency record an obligation when there is sufficient documentary evidence of the government's liability. See, e.g., B‑329712, Oct. 15, 2020. The statute also specifies the type of documentary evidence necessary to record an obligation for different types of transactions. 31 U.S.C. § 1501(a).

In particular, the statute requires agencies to record an obligation based on documentary evidence of a grant or subsidy payable from appropriations that is “required to be paid in specific amounts fixed by law or under formulas prescribed by law.” 31 U.S.C. § 1501(a)(5)(A). We have consistently determined that this provision applies when a statute requires the government to provide federal assistance and prescribes a formula to calculate the payments, see, e.g., B-316915, Sept. 25, 2008, even if the statute does not characterize the payments as a “grant” or “subsidy.” See 63 Comp. Gen. 525 (1984) (involving “allotments” to states); B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983 (involving “payments” to local governments).

The Food and Nutrition Act requires SNAP benefits to be paid to eligible households (as identified by each state) based on a specified formula, subject to the availability of appropriations. 7 U.S.C. §§ 2013(a) (authorizing SNAP “[s]ubject to the availability of funds appropriated under” the Act), 2014(a) (providing that “[a]ssistance under this program shall be furnished to all eligible households who make application for such participation”), 2017 (prescribing the formula for calculating a household's monthly allotment), 2027(b) (prohibiting the issuance of benefits in excess of the amount appropriated); see A-51604, Apr. 3, 1979 (examining the previous food stamp program and noting that “[o]nce a household is determined to be eligible for an allotment on the basis of uniform national standards, [USDA] is required to furnish such a household with assistance if it applies for participation under the program”). Because the government is required to provide SNAP benefits in specific amounts under a formula prescribed by law, USDA should record obligations for SNAP benefits in accordance with section 1501(a)(5)(A) of title 31.[21]

The next question is at what point does USDA incur an obligation for SNAP benefits. In FY 2023, USDA initially treated the point of obligation for SNAP benefits as the day such benefits were issued.[22] Then, in September 2023, USDA changed its practice and treated its letter to the Federal Reserve Bank as the point of obligation for SNAP benefits.[23]

Under section 1501(a)(5)(A), an agency must record an obligation when supported by documentary evidence of federal assistance payable from appropriations that is required to be paid in specific amounts fixed by law or under formulas prescribed by law. See B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983; B-316915, Sept. 25, 2008. For programs covered by section 1501(a)(5)(A) that are funded by one-year appropriations, the point of obligation is generally when appropriations for such payments have been enacted and are available for obligation. See GAO, Tracking the Funds: Specific Fiscal Year 2022 Provisions for Federal Agencies, GAO‑22‑105467 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2022), at 30 (citing B‑316915, Sept. 25, 2008) (noting that “in some circumstances the obligational event occurs immediately when the appropriation for the grant becomes law”).[24] In these cases, the underlying statute and the appropriation create a legal liability or a legal duty that could mature into a legal liability by virtue of actions taken by other parties beyond the control of the government.

For example, in B-212145, we examined a statute requiring the Secretary of the Interior to make payments each fiscal year to local governments in which certain federal lands were located. B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983. We determined that the criteria for recording an obligation in section 1501(a)(5)(A) were met by virtue of the authorizing legislation requiring annual payments using a specified formula and the enactment of appropriations for that particular fiscal year. Id.

In another decision, we looked at a statutory program administered by the Election Assistance Commission (EAC). B-316915, Sept. 25, 2008. The statute directed EAC to make payments to states under a prescribed formula, provided that the state certified that it met certain statutory requirements. Id. We noted that Congress had appropriated amounts for the particular year at issue and concluded that EAC incurred an obligation for the grant payments for that fiscal year by operation of law, regardless of when or if a particular state submitted a certification, because the states had the ability to fulfill the preconditions without any action on the part of the agency. Id.

SNAP is considered an appropriated entitlement, meaning that the government is legally required to make payments to those who meet the program requirements and funding is provided by annual appropriations acts. See OMB Response, at 3 & n.2 (citing H.R. Rep. No. 105-217 (1997) and OMB, Circular No. A-11, Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget, §§ 20.3, 123.11 (July 2024)). The Food and Nutrition Act imposes a legal duty on USDA that could mature into a legal liability for SNAP benefit payments by virtue of actions taken by program participants (such as applying for SNAP benefits) and states (such as determining household eligibility and benefit amounts) that are beyond the control of USDA, but conditions USDA's liability on the availability of appropriations for these payments.[25] Accordingly, the point of obligation for SNAP benefits generally occurs when appropriations for the benefits are enacted and available for obligation. USDA therefore incorrectly treated each day SNAP benefits were issued and, later, its September 19, 2023, letter to the Federal Reserve Bank, as the point of obligation for SNAP benefits in violation of the recording statute.

USDA does not explain in its response how its previous practice, namely treating each day that benefits were issued as the point of obligation, comported with the recording statute and simply states that it was unaware of any legal analysis of the previous practice.[26] With respect to its new practice, USDA states that the point of obligation is the issuance of the letter to the Federal Reserve Bank reflecting the maximum amount of funds available to states for SNAP benefits.[27] USDA states that this is because the letter quantifies and memorializes the benefit amounts.[28]

USDA's position is inconsistent with our previous decisions concluding that obligations described in section 1501(a)(5)(A) arise by operation of law and not as a result of agency action. Compare B-316915, Sept. 25, 2008 (concluding that an agency's obligation arose by operation of law within the meaning of section 1501(a)(5)(A)), with B-316372, Oct. 21, 2008 (concluding that an agency incurred an obligation within the meaning of a different provision of the recording statute, section 1501(a)(5)(B), when it transmitted a grant award to the recipient). Although USDA's failure to issue the letter to the Federal Reserve Bank may have affected whether benefits were paid, such action did not affect USDA's underlying liability for the benefits established by the Food and Nutrition Act and the relevant appropriation. See B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983 (concluding that an agency incurred an obligation within the meaning of section 1501(a)(5)(A) based on a statute requiring payments and the availability of appropriations for such payments, notwithstanding that the agency had to take additional action, namely identifying specific recipients and amounts due, before making those payments).[29]

(2) Amount Recorded

The recording statute requires an agency to record the full amount of its obligation against funds available at the time it incurs the obligation. See, e.g., B‑327242, Feb. 4, 2016. As discussed above, the point of obligation for SNAP benefits is generally when an appropriation for those benefits is enacted and available for obligation.

With respect to entitlements and other programs described in section 1501(a)(5)(A), the government's obligation “is the full amount required for payment under the applicable statute, even though that actual amount may not be finally determined until later.” 65 Comp. Gen. 4 (1985); see 63 Comp. Gen. 525 (1984); B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983; B-164031(3).150, Sept. 5, 1979. This includes programs, like SNAP, where the number of beneficiaries fluctuates based on external factors like economic conditions.[30] See 65 Comp. Gen. 4 (1985) (examining a program where, because “the number of eligible beneficiaries [would] vary—depending on external factors—the exact amount of the [g]overnment's obligation [could not] be determined in advance”). For these programs, “the appropriate amount to be recorded initially as an obligation is the agency's best estimate of the [g]overnment's ultimate liability under the relevant entitlement legislation.” 65 Comp. Gen. 4 (1985); see 63 Comp. Gen. 525 (1984); B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983. The agency should subsequently adjust the recorded amount as necessary, 65 Comp. Gen. 4 (1985), such as when specific recipients and exact payment amounts become known. B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983.

In determining the scope of USDA's ultimate liability for SNAP benefits and the amount to record, we look to the provisions of the Food and Nutrition Act. The Act states that SNAP benefits are subject to the availability of appropriations. 7 U.S.C. § 2013(a). In particular, the Act requires that “[i]n any fiscal year, the Secretary [of Agriculture] shall limit the value of those allotments issued to an amount not in excess of the appropriation for such fiscal year.” 7 U.S.C. § 2027(b). If, in any fiscal year, the Secretary finds that the allotments will exceed the appropriation, the Secretary shall direct the states to reduce allotments to the extent necessary to comply with the statutory limitation. Id.

The Food and Nutrition Act therefore ties SNAP benefits for a particular fiscal year to the appropriation for that fiscal year, limiting such benefits to the amount appropriated for the year. This limitation, in effect, establishes the scope of USDA's liability. With respect to SNAP, once an appropriation is enacted and available for obligation, USDA's liability is limited to SNAP benefits for the current fiscal year.[31]

This interpretation is consistent with our previous decisions examining programs for which liability arises by operation of law and are funded annually with one-year appropriations. In B‑212145 and B-316915, the relevant authorizing legislation provided for payments for each fiscal year, and programs were funded with one-year appropriations. B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983 (citing 31 U.S.C. § 6902 (1983)); Pub. L. No. 97-394, title I, 96 Stat. 1966, 1966 (Dec. 30, 1982); B‑316915, Sept. 25, 2008 (citing 42 U.S.C. §§ 15401, 15403 (2008)); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-161, div. D, title V, 121 Stat. 1844, 1996 (Dec. 26, 2007). In both decisions, we determined that an obligation arose by operation of law with respect to payments for the fiscal year covered by the appropriation. B‑212145, Sept. 27, 1983; B-316915, Sept. 25, 2008.

Considering both the requirements of the recording statute and the provisions of the Food and Nutrition Act, when an appropriation for SNAP is enacted and available for obligation, USDA must record its best estimate of the agency's total liability for SNAP benefits for the fiscal year covered by the appropriation and then adjust that amount as necessary.

USDA's initial practice of recording obligations daily violated the recording statute with respect to the amount recorded because USDA did not record its best estimate of its total liability for SNAP benefits issued during the entire fiscal year; rather, it only recorded the amount of SNAP benefits issued on a particular day.

USDA also violated the recording statute with respect to the amount recorded for the September 19, 2023, obligation. Specifically, USDA recorded an obligation against its FY 2023 one-year appropriation in an amount that included October 2023 SNAP benefits. But, as discussed above, USDA's liability for SNAP benefits in FY 2023 was limited to benefits owed for FY 2023 and did not include the October 2023 benefits. Instead, USDA should have recorded an obligation for the October 2023 benefits against its FY 2024 SNAP appropriation when that appropriation was enacted and available for obligation.[32]

Bona Fide Needs Statute

The bona fide needs statute states that a time-limited appropriation is available only to pay for obligations properly incurred during the appropriation's period of availability. 31 U.S.C. § 1502(a). An obligation is “properly incurred” if it fulfills a genuine or “bona fide” need that exists during the period of availability of the appropriation. See, e.g., B-326945, Sept. 28, 2015. Unless otherwise provided, an agency may not use an appropriation to pay for obligations that are properly incurred after the appropriation expires. See B-308944, July 17, 2007; B‑164031(3).150, Sept. 5, 1979 (stating that “a prior year's appropriation, even if some amount remains unobligated, cannot be applied to expenditures . . . in the current fiscal year”); B‑286929, Apr. 25, 2001 (noting that “[n]othing in the bona fide needs rule suggests that expired appropriations may be used for a project for which a valid obligation was not incurred prior to expiration”).

Compliance with the bona fide needs statute is measured at the time the agency incurs an obligation and depends on the purpose of the transaction and the nature of the obligation. B-333150, Apr. 8, 2024; B-289801, Dec. 30, 2002 (citing 61 Comp. Gen. 184 (1981)). When an agency incurs an obligation by taking some action, such as entering into a contract or awarding a grant, determining compliance with the bona fide needs statute often focuses on whether the obligation fulfills a bona fide need existing during the relevant appropriation's period of availability and was thus “properly incurred.” See, e.g., B-332430, Sept. 28, 2021; B-289801, Dec. 30, 2002. In contrast, when an obligation arises by operation of law, there is no question that the obligation was properly incurred, and our decisions instead focus on: (1) when the obligation arose; and (2) whether the agency paid for the obligation with an appropriation that was available at that time. See B-226801, Mar. 2, 1988; see also B‑164031(3).150, Sept. 5, 1979 (analyzing agency compliance with an earlier version of the statute).

As explained above, the point of obligation for SNAP benefits is when appropriations are enacted and available for obligation. And the Food and Nutrition Act establishes that USDA's liability for SNAP benefits is limited to the benefits for the current fiscal year. See 7 U.S.C. § 2027(b). In other words, when USDA's FY 2023 SNAP appropriation was enacted and available for obligation, USDA incurred an obligation for FY 2023 SNAP benefits (up to the amount appropriated for the year). USDA then incurred an obligation for FY 2024 SNAP benefits in FY 2024 when appropriations for that year were enacted and available for obligation.

With respect to USDA's initial practice of recording obligations on a daily basis, there was no bona fide needs statute violation. Although the practice did not comply with the recording statute, both with respect to the point of obligation and the obligation amount, USDA used its FY 2023 one-year appropriation to pay for FY 2023 benefits in compliance with the bona fide needs statute.

In contrast, USDA violated the bona fide needs statute when it used its FY 2023 one-year SNAP appropriation to pay for benefits issued to households in FY 2024. As discussed above, notwithstanding USDA's attempt to record an obligation for the October 2023 benefits in FY 2023, USDA did not incur an obligation for those benefits until FY 2024. Therefore, USDA could not use its FY 2023 one-year appropriation to pay for the October 2023 benefits.

In their responses, USDA and OMB state that a bona fide need to obligate funds for October 2023 benefits existed in FY 2023.[33] USDA points to GAO decisions concluding that, in the federal assistance context, the agency's need is fulfilled when it makes the award, regardless of when the recipient will expend the funds.[34] USDA further states (and OMB agrees) that given the lead time and preliminary steps necessary to facilitate payments, there was a need to send the Federal Reserve Bank letter and obligate funds for the October 2023 benefits in FY 2023.[35]

The previous GAO decisions cited by USDA addressed situations in which the agency incurred an obligation by issuing a grant award or entering into a cooperative agreement. See B-289801, Dec. 30, 2002 (grant); B-229873, Nov. 29, 1988 (cooperative agreement). In those decisions, agency action created an obligation, and the question was whether the obligation fulfilled a bona fide need existing during the period of availability of the appropriation charged. See B‑289801, Dec. 30, 2002; B-229873, Nov. 29, 1988.

Unlike the programs at issue in the cited decisions, the obligations for SNAP benefits arise by operation of law rather than from agency action. As described above, our analysis differs for those types of obligations. Instead of looking at whether the obligation was “properly incurred,” we look at when the obligation arose and whether USDA paid for the obligation with an appropriation available at that time. As discussed above, USDA incurred an obligation by operation of law for the October 2023 SNAP benefits in FY 2024. Because the obligation arose in FY 2024, the FY 2023 one‑year SNAP appropriation was not available to pay for the obligation. However, nothing in this decision precludes USDA, the Federal Reserve Bank, or states from taking actions at the end of the fiscal year to prepare for the issuance of benefits at the beginning of the new fiscal year, though, as prescribed by the Food and Nutrition Act, USDA's authority to make funds available for benefits will depend on the availability of appropriations in the new fiscal year.

Antideficiency Act

The Antideficiency Act prohibits agencies from obligating or expending in excess of, or obligating in advance of, an available appropriation unless otherwise authorized by law. 31 U.S.C. § 1341(a). And, unless otherwise provided, appropriations are not available to liquidate obligations incurred before or after the appropriation's period of availability. See B-226801, Mar. 2, 1988; GAO, Anti-Deficiency Act: Agriculture's Food and Nutrition Service Violates the Anti-Deficiency Act, GAO/AFMD-87-20 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 1987) (concluding that USDA violated the Antideficiency Act when the agency used its appropriation for Child Nutrition Programs to liquidate obligations for meals served at the end of the previous fiscal year).[36]

Here, USDA incurred obligations for October 2023 SNAP benefits in FY 2024 when FY 2024 appropriations were enacted and available for obligation. However, USDA incorrectly recorded an obligation for those benefits against its FY 2023 one-year appropriation and used that appropriation to liquidate the obligation. Nothing in the Food and Nutrition Act or the SNAP appropriation authorizes USDA to use its one‑year appropriation to liquidate obligations for SNAP benefits incurred in future fiscal years, and, therefore, USDA was not permitted to expend funds from its FY 2023 one-year appropriation to pay for the October 2023 benefits.[37]

USDA should adjust its accounts by charging the October 2023 benefits to SNAP appropriations available for obligation in FY 2024. Should USDA lack sufficient amounts in these appropriations to cover the October 2023 benefits, it must report an Antideficiency Act violation to the President and Congress, with a copy of the report to the Comptroller General.

CONCLUSION

USDA violated the recording statute with respect to the point of obligation and amount recorded for SNAP benefits. USDA should have recorded obligations for FY 2023 SNAP benefits when appropriations for those benefits were enacted and available for obligation, not when benefits were issued or later in the year when USDA communicated to the Federal Reserve Bank the amount of funds available for benefits. With respect to the amount recorded for its liability for FY 2023 SNAP benefit payments, USDA should have recorded its best estimate of the total amount of FY 2023 SNAP benefits. USDA violated the recording statute when it continuously recorded the amount of benefits issued each day and, later, when it recorded an amount that included some FY 2024 benefits.

While USDA's original practice for recording obligations during FY 2023 was consistent with the bona fide needs statute, USDA violated that statute when it used its FY 2023 one-year SNAP appropriation to pay for FY 2024 SNAP benefits. USDA should adjust its accounts by charging those benefits to SNAP appropriations available for obligation in FY 2024. Should USDA lack sufficient amounts in these appropriations to cover the FY 2024 benefits, it must report an Antideficiency Act violation.

Edda Emmanuelli Perez

General Counsel

Attachment

SNAP Obligations

[1] Letter from Counsel to the Inspector General, USDA OIG, to General Counsel, GAO (Feb. 16, 2024).

[2] USDA OIG, USDA's Consolidated Financial Statements for Fiscal Years 2023 and 2022, Audit Report 50401-0022-11 (Jan 16, 2024), available at https://usdaoig.oversight.gov/reports/audit/usdas-consolidated-financia… (last visited Feb. 3, 2025).

[3] GAO, GAO's Protocols for Legal Decisions and Opinions, GAO-24-107329 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 2024), available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-107329; Letter from Assistant General Counsel for Appropriations Law, GAO, to Principal Deputy General Counsel, USDA (Apr. 10, 2024).

[4] USDA, USDA Response to GAO B-336036: U.S. Department of Agriculture—Application of Recording Statute, Bona Fide Needs Statute, and Antideficiency Act to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Benefits (June 13, 2024) (with attachments) (USDA Response).

[5] Email from Assistant General Counsel for Appropriations Law, GAO, to General Counsel, OMB, Subject: Seeking OMB GC's views regarding obligations for SNAP benefits (July 10, 2024); Letter from Assistant General Counsel, OMB, to Assistant General Counsel for Appropriations Law, GAO (Aug. 22, 2024) (with attachments) (OMB Response).

[6] 7 U.S.C. §§ 2011–2029, 2031–2032, 2034–2036b, 2036d.

[7] GAO, Improper Payments: USDA's Oversight of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, GAO-24-107461 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2024), at 2.

[8] GAO, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Actions Needed to Better Measure and Address Retailer Trafficking, GAO-19-167 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 2018) (2018 GAO Report), at 3; see USDA Response, at 2–3, Attachments C, F.

[9] USDA Response, at 3.

[10] See id. at 2–3, Attachment C.

[11] Id. at 3.

[12] 2018 GAO Report, at 3; see USDA Response, at 3.

[13] USDA Response, at 1; see, e.g., Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, Pub. L. No. 117-328, div. A, tit. IV, 136 Stat. 4459, 4488–89 (Dec. 29, 2022).

[14] USDA Response, at 1; see, e.g., Pub L. No. 117-328, 136 Stat. at 4488–89.

[15] USDA Response, at 3–4.

[16] Id.

[17] Id. at 4, 6.

[18] Id. at 6.

[19] Id. at Attachment F. We have attached to this decision a chart illustrating USDA's recording practices during FY 2023.

[20] Id.

[21] Both USDA and OMB agree that section 1501(a)(5)(A) applies to SNAP benefits, though they state in their responses that the recording statute's catchall provision (section 1501(a)(9)) may also apply. See USDA Response, at 8–9, Attachment F; OMB Response, at 3.

[22] USDA Response, at 3–4.

[23] Id. at 4, 6.

[24] Neither the Food and Nutrition Act nor the SNAP appropriation specifies an alternative point of obligation.

[25] One way USDA exercises control over its liability is its approval of state plans of operation to participate in SNAP. 7 U.S.C. § 2020(d); 7 C.F.R. § 272.2. However, neither USDA nor OMB suggests that there were any states that did not already have approved plans in place when appropriations for FY 2023 were enacted and available for obligation. See USDA Response; OMB Response.

[26] USDA Response, at 4.

[27] USDA Response, at 8–9.

[28] Id. at 8–9.

[29] In a 2019 decision, we examined SNAP benefit obligations recorded by USDA during a lapse in appropriations. B-331094, Sept. 5, 2019. At the time, USDA was initially recording obligations for SNAP benefits on a daily basis and then deviated from this practice by recording obligations for February 2019 SNAP benefits in January 2019. Id. We concluded that USDA lacked authority under the most recent continuing resolution (CR) to record those obligations against the CR appropriation. Id. Our focus in B-331094 was USDA's obligations during the CR period and whether those obligations violated the Antideficiency Act. See id. In line with previous decisions examining agency practices during CRs, we compared USDA's actions during the CR period with the agency's normal practice for recording obligations and concluded that USDA was not authorized to change its practice. Id. We thus did not, and had no reason to, make a determination as to whether USDA's normal practice of obligating SNAP benefits on a daily basis comported with the recording statute. Examining that issue in this decision, we conclude that the practice violated the statute.

[30] See USDA, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): Key Statistics and Research, available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/supplemental-… (last visited Feb. 3, 2025) (noting that economic downturns result in increased SNAP participation and benefit sizes).

[31] If the total amount of SNAP benefits for a particular fiscal year exceeds the one-year SNAP appropriation, or if a one-year SNAP appropriation is not available due to a lapse, USDA may use available amounts in the SNAP contingency fund to provide benefits. See B-331094, Sept. 5, 2019 (noting the availability of the SNAP contingency fund for SNAP benefit obligations when other budget authority was not available due to a lapse in appropriations).

[32] At the beginning of FY 2024, USDA had available budget authority for the October 2023 SNAP benefits by virtue of a continuing resolution. See Continuing Appropriations Act, 2024 and Other Extensions Act, Pub. L. No. 118-15, 137 Stat. 71 (Sept. 30, 2023).

[33] USDA Response, at 9–11; OMB Response, at 4.

[34] USDA Response, at 10–11.

[35] Id.; OMB Response, at 4.

[36] We have previously stated that the prohibitions with respect to obligations are directed at discretionary obligations entered into by agency officers, 65 Comp. Gen. 4 (1985), and recognized that Congress may implicitly authorize an agency to incur obligations in excess of its appropriation by virtue of a law that necessarily requires such obligations. B‑329712, Oct. 15, 2020; B-262069, Aug. 1, 1995. To confer such authority, the statute must require the agency to incur the obligation regardless of the availability of sufficient appropriations. B-329712, Oct. 15, 2020. Although the Food and Nutrition Act requires the payment of SNAP benefits, such payment is expressly subject to the availability of appropriations, 7 U.S.C. §§ 2013(a), 2027(b), and the Act therefore does not authorize USDA to incur obligations or make expenditures for such benefits in excess of its appropriations. Cf. B-331094, Sept. 5, 2019 (concluding that USDA was not authorized to incur certain SNAP benefit obligations without available budget authority).

[37] Although our analysis of USDA's SNAP benefit obligations differed somewhat in B‑331094, our determination in that decision is consistent with our conclusions here. See B‑331094, Sept. 5, 2019. In that decision, we found that the relevant CR language limited the scope of SNAP benefits payable from the CR appropriation to those benefits due within a certain time period. Id. Thus, in the same way that USDA's FY 2023 one-year SNAP appropriation was not available to pay for FY 2024 SNAP benefits, the CR appropriation at issue in B‑331094 was not available to pay for benefits due after the period prescribed in the CR.