Educational Opportunities and Discipline Issues in Public Schools on the 65th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education

On May 17, 1954, in its Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously held that state laws establishing “separate but equal” public schools for Blacks and Whites were unconstitutional.

Sixty-five years later, race and poverty still are issues in our nation’s public schools, as our work on school composition, discipline, and access to courses that prepare students for college has highlighted.

In today’s WatchBlog, we share some findings from a few of our recent reports examining the intersection of race and poverty in public K-12 schools.

Racial and socioeconomic isolation is increasing

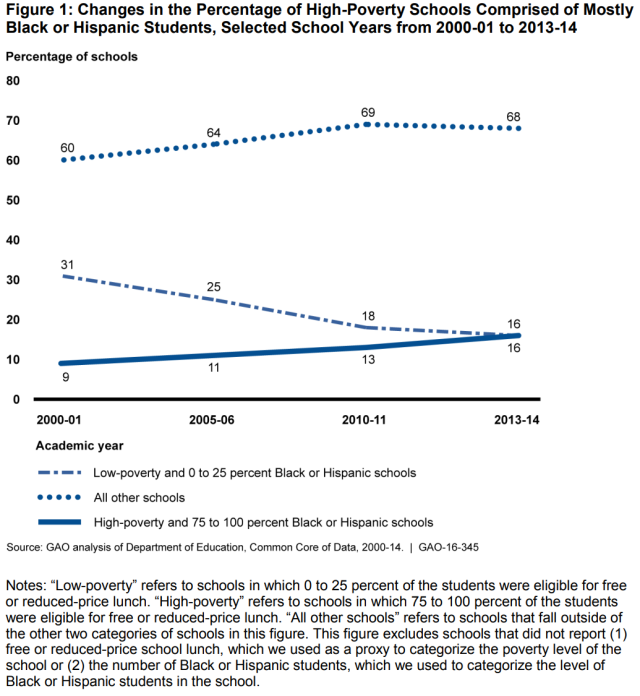

In our 2016 report, we found that over time, there has been a large increase in schools that are the most isolated by poverty and race. From 2000-14, the percentage of K-12 public schools that were both high poverty and comprised of mostly Black or Hispanic students grew significantly.

In these schools, 75-100% of the students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, and 75-100% of the students were Black or Hispanic.

During the same time, the number of students attending these schools also grew. For instance, the number of students attending high-poverty, mostly Black or Hispanic, schools more than doubled.

Discipline disproportionately affects certain groups of students

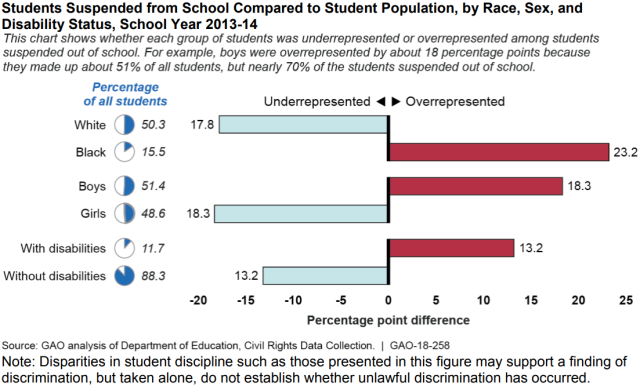

In our 2018 report, we found that Black students, boys, and students with disabilities were disproportionately disciplined in K-12 public schools, based on data from the 2013-14 school year. This pattern persisted regardless of the level of school poverty, type of public school, and type of disciplinary action, including:

- in-school and out-of-school suspensions;

- referrals to law enforcement;

- expulsions;

- corporal punishment; and

- school-related arrests.

Fewer course offerings; fewer educational opportunities

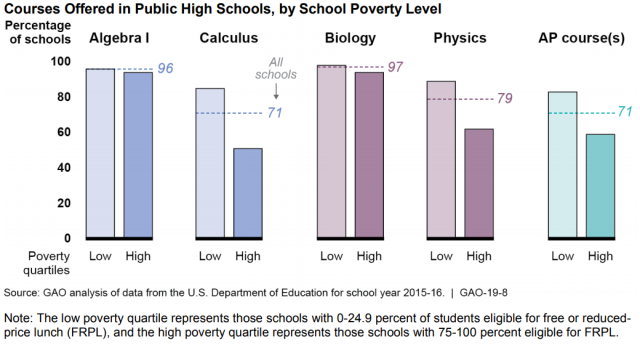

Students in relatively poor and small schools also had less access to high school courses that help prepare them for college, according to our analysis of data from the 2015-16 school year.

While most public high schools, regardless of poverty level, offered courses like algebra and biology, students in high-poverty schools tended to have less access to more advanced courses like calculus, physics, and those that may allow students to earn college credit, like Advanced Placement (AP) courses.

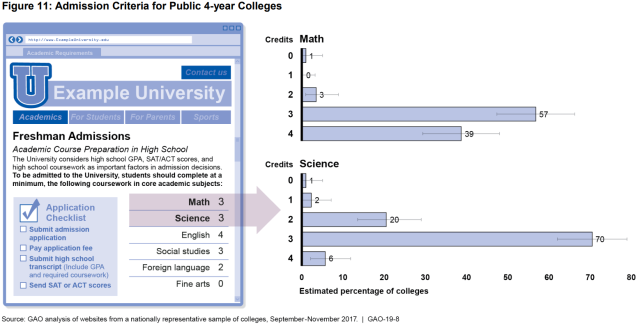

This poses a problem for students applying to colleges. For example, a majority of colleges wanted their students to have at least 3 math courses and at least 3 science courses. Some also preferred that their students had some exposure to AP courses.

However, if students don’t have access to these courses, they may have a disadvantage in getting into colleges. When it came to math, 17% of high-poverty schools did not offer enough courses for a student to fulfill these college recommendations. For science, the numbers were even grimmer: 41% of the high-poverty schools did not offer all the science courses a student would need to meet admission expectations.

As we approach the 65th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, this work shows that disparities still exist. These disparities among types and groups of schools may limit the educational opportunities available to poor and minority students.

Comments on GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact blog@gao.gov.