Innovative Design in Federal Buildings

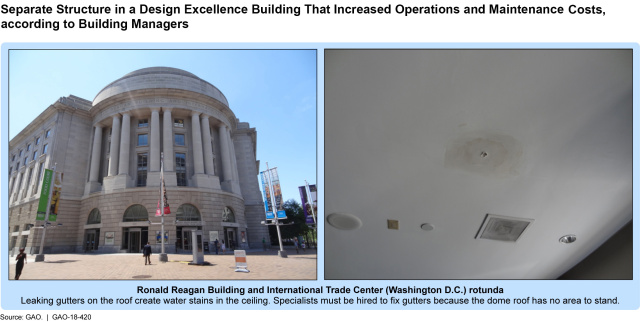

However, other design choices, such as separate structures (like rotundas), custom windows, and multi-story atriums, led to higher maintenance costs. For instance, the rotunda in the Ronald Reagan Building in Washington, D.C., had water stains on the ceiling from leaking roof gutters. And while fixing gutters is a common maintenance activity, specialists had to be hired to fix these gutters because the dome roof has no area to stand.

However, other design choices, such as separate structures (like rotundas), custom windows, and multi-story atriums, led to higher maintenance costs. For instance, the rotunda in the Ronald Reagan Building in Washington, D.C., had water stains on the ceiling from leaking roof gutters. And while fixing gutters is a common maintenance activity, specialists had to be hired to fix these gutters because the dome roof has no area to stand.

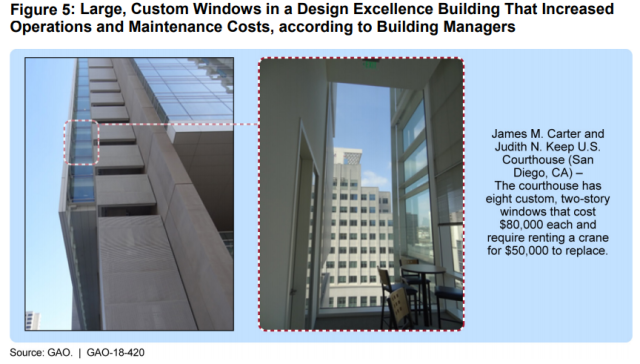

GSA officials at one courthouse reported repairing a two-story, custom-made window pane, which cost $80,000 to fabricate and $50,000 to install.

GSA officials at one courthouse reported repairing a two-story, custom-made window pane, which cost $80,000 to fabricate and $50,000 to install.

Multistory atriums often led to additional costs, including the need to erect expensive scaffolding for maintenance.

Multistory atriums often led to additional costs, including the need to erect expensive scaffolding for maintenance.

Blueprint for the future

Undertaking operations and maintenance activities will cost more than initial construction over the life of a building. Consequently, decisions made during the planning and design process can result in cost-savings—or unexpected expenses.

However, we found that GSA did not fully factor operations and maintenance costs into their building planning process. Instead, the agency:

Blueprint for the future

Undertaking operations and maintenance activities will cost more than initial construction over the life of a building. Consequently, decisions made during the planning and design process can result in cost-savings—or unexpected expenses.

However, we found that GSA did not fully factor operations and maintenance costs into their building planning process. Instead, the agency:

- Only considered the operations and maintenance costs of large systems that required energy

- Did not consistently gather or use input from staff with operations and maintenance experience

- Did not ensure information on lessons learned was shared

- Questions on the content of this post? Contact Lori Rectanus at rectanusl@gao.gov.

- Comments on GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact blog@gao.gov.

GAO's mission is to provide Congress with fact-based, nonpartisan information that can help improve federal government performance and ensure accountability for the benefit of the American people. GAO launched its WatchBlog in January, 2014, as part of its continuing effort to reach its audiences—Congress and the American people—where they are currently looking for information.

The blog format allows GAO to provide a little more context about its work than it can offer on its other social media platforms. Posts will tie GAO work to current events and the news; show how GAO’s work is affecting agencies or legislation; highlight reports, testimonies, and issue areas where GAO does work; and provide information about GAO itself, among other things.

Please send any feedback on GAO's WatchBlog to blog@gao.gov.