Understanding Derivatives One Swap at a Time

Did you ever agree to swap your PB&J sandwich for your friend’s bologna sandwich? If so, you did a nonfinancial swap.

Since the 1980s, bankers have applied that basic concept to create financial contracts to swap a wide range of stuff—from interest rates to commodities to credit risk—you name it.

Commercial firms use swaps to manage risk. For example, airline companies use swaps to lock in their fuel prices to protect their profits against rises in fuel prices.

Swaps and other over-the-counter financial contracts whose value is derived from something else (called derivatives) have ballooned into a multitrillion-dollar market worldwide.

At the same time, these derivatives contributed to the 2007—2009 financial crisis, as illustrated by the failure of Lehman Brothers and AIG’s near failure.

We reported on steps taken to address risks raised by over-the-counter derivatives through the Dodd-Frank Act. Today’s WatchBlog shares what we found.

Where do you “buy” swaps?

Despite their name, swaps are not sold at swap meets; instead, firms enter into swaps through swap dealers—large financial institutions with the capital and expertise to do such transactions.

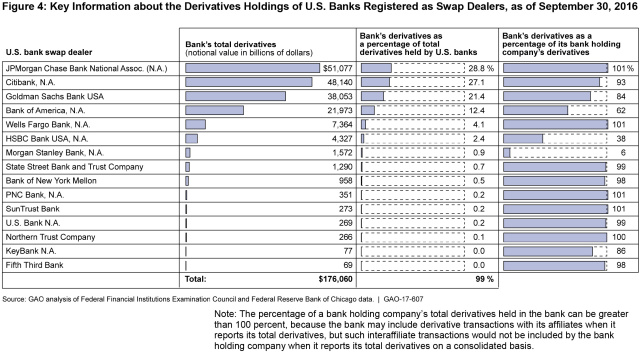

Similar to other contracts, swaps are privately negotiated between a firm and a swap dealer. Of the approximately 5,700 banks, 15 of them are swap dealers, and they held around $176 trillion in derivatives. That is around 99 percent of the derivatives held by all U.S. banks! And the top four banks held almost 90 percent of the total.

How are swaps used?

According to a 2009 survey, 94 percent of the world’s 500 largest companies use derivatives to manage their business and financial risks. For example, companies use swaps to manage risk from unfavorable changes in interest rates, commodity prices, or security prices.

Alternatively, hedge funds or others use swaps to speculate, such as on the direction of equity markets, to make a profit. Under swaps, the two parties typically exchange payments based on price changes in the amount of the thing or things being swapped over a specified period.

How were swaps a problem in the 2007—2009 crisis?

Swaps and other over-the-counter derivatives contributed to the 2007—2009 financial crisis partly by helping to allow excessive risk taking, creating uncertainty about exposure to risk, and causing a loss in market confidence.

A swap party faces credit risk because the other party may not pay the amount owed under the swap when due. Before the Dodd-Frank Act, swap parties were not required by regulations to post cash or other collateral (called margin) to reduce credit risk. This allowed some to take large speculative positions using a relatively small amount of capital, exposing their dealers to considerable risk.

Moreover, swaps increased the financial system’s interconnectedness by exposing many swap parties to the credit risk of a few swap dealers. The concentration created the risk that a dealer’s failure could cause swap parties to suffer sudden losses and destabilize financial markets.

How did the Dodd-Frank Act address the swaps problem?

In addition to subjecting large banks to heightened standards for safety and soundness, the Dodd-Frank Act established a new regulatory framework for swaps with the goals of reducing risk, increasing transparency, and promoting market integrity in the financial system. Specifically, the act included the following swaps reforms:

- Swap dealers must register with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission or Securities and Exchange Commission and be subject to regulations to ensure their safety and soundness, such as minimum capital and margin requirements.

- Certain swaps must be cleared through a central clearing house and traded on an exchange, and

- Swaps must be reported to a registered swap data repository.

- Comments on GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact blog@gao.gov.

GAO Contacts

Related Products

GAO's mission is to provide Congress with fact-based, nonpartisan information that can help improve federal government performance and ensure accountability for the benefit of the American people. GAO launched its WatchBlog in January, 2014, as part of its continuing effort to reach its audiences—Congress and the American people—where they are currently looking for information.

The blog format allows GAO to provide a little more context about its work than it can offer on its other social media platforms. Posts will tie GAO work to current events and the news; show how GAO’s work is affecting agencies or legislation; highlight reports, testimonies, and issue areas where GAO does work; and provide information about GAO itself, among other things.

Please send any feedback on GAO's WatchBlog to blog@gao.gov.