Drinking Water: Additional Data and Statistical Analysis May Enhance EPA's Oversight of the Lead and Copper Rule

Fast Facts

No level of lead is safe in drinking water. Lead accumulates in the body over time, causing long-lasting effects, particularly for children and pregnant women.

The Lead and Copper Rule generally requires water systems to test for lead and treat water to help prevent corroded pipes from leaching lead into the water. The 68,000 water systems serving the majority of U.S. residents are subject to the rule, and must test in high-risk areas near lead pipes. However, many lead pipe locations are unknown.

We recommended that the Environmental Protection Agency collect data on lead pipes, among other things, to improve its oversight of the rule.

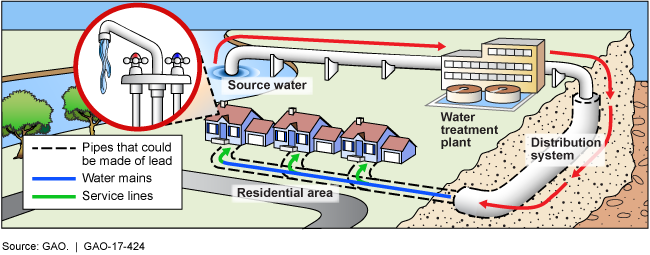

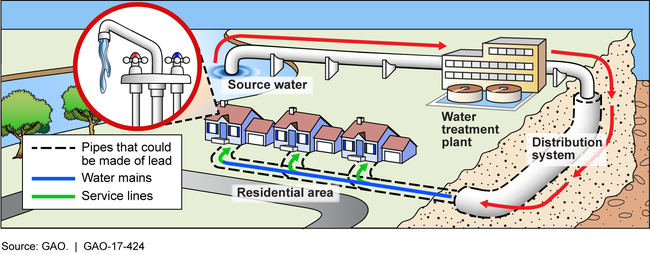

Example of Potential Lead in the Pipe Infrastructure from Source to Homes

A cutaway illustration of a water system showing where pipes could be made of lead.

Highlights

What GAO Found

Available Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data, reported by states, show that of the approximately 68,000 drinking water systems subject to the Lead and Copper Rule (LCR), at least 10 percent had at least one open violation of the rule; however these and other data are not complete. When the LCR was promulgated in 1991, all water systems were required to collect information about the infrastructure delivering water to customers, including lead pipes (see figure). However, because the LCR does not require states to submit information on known lead pipes to EPA, the agency does not have national-level information about lead infrastructure. After the events in Flint, Michigan, and other cities, EPA asked states to collect information on the locations of lead pipes, and all but nine, which had such difficulties as finding historical documentation, indicated a plan or intent to fulfill the request. According to EPA guidance, knowledge of lead pipes is needed for studies of corrosion control. GAO reported in March 2013 that with limited funding for federal programs, the need to target such funds efficiently increases. By EPA requiring states to report data on lead pipes, key decision makers would have information about the nation's lead infrastructure.

Example of Potential Lead in the Pipe Infrastructure from Source to Homes

Through discussion groups, state regulators identified 29 factors that may contribute to water systems' noncompliance with the LCR. In conducting a statistical analysis using EPA data on selected factors, such as the size of the population served and type of source water, GAO found that such factors were associated with a higher likelihood of water systems having reported violations of the LCR. EPA's current approach to oversight of the LCR targets water systems with sample results that exceed the lead action level. While this approach is reasonable because such water systems have a documented lead exposure risk, EPA officials in 3 of the 10 regional offices told GAO that it is not sustainable over time because of limited resources. Under federal standards for internal control, management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the defined objectives. By developing a statistical analysis that incorporates multiple factors to identify water systems that might pose a higher likelihood for having reported violations of the LCR to supplement its current approach, EPA could better target its oversight to such water systems.

Why GAO Did This Study

Drinking water contaminated with lead in Flint, Michigan, renewed awareness of the danger lead poses to the nation's drinking water supply. Lead exposure through drinking water is caused primarily by the corrosion of plumbing materials, such as pipes, that carry water from a water system to pipes in homes. EPA set national standards to reduce lead in drinking water with the LCR, which applies to all water systems providing drinking water to most of the U.S. population, except places where people do not remain for long, such as campgrounds. States generally have primary responsibility for enforcing the LCR, and data help EPA monitor states' and systems' compliance with the LCR.

GAO was asked to review the issue of elevated lead in drinking water. Among other objectives, this report examines (1) what available EPA data show about LCR compliance among water systems and (2) factors that may contribute to LCR noncompliance. GAO analyzed EPA data on violations and enforcement of the LCR from July 1, 2011, through December 31, 2016, interviewed EPA officials in headquarters and the 10 regional offices; conducted a statistical analysis of the likelihood of reported LCR violations; and held discussion groups with a nonprobability sample of regulators representing 41 states.

Recommendations

GAO is making three recommendations, including for EPA to require states to report data on lead pipes and develop a statistical analysis on the likelihood of LCR violations to supplement its current oversight. EPA agreed with GAO's recommendations.

Recommendations for Executive Action

| Agency Affected | Recommendation | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Protection Agency |

Priority Rec.

The Assistant Administrator for Water of EPA's Office of Water should require states to report available information about lead pipes to EPA's Safe Drinking Water Information System (SDWIS)/Fed (or a future redesign such as SDWIS Prime) database, in its upcoming revision of the LCR. (Recommendation 1) |

On January 15, 2021, EPA issued a final regulation revising the Lead and Copper Rule that, once in effect, would implement this recommendation. The final rule would require states to report quarterly to EPA on the number of lead service lines each public water system in the state has. We closed this recommendation as implemented after the rule went into effect on December 16, 2021. For more information see EPA's website: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/review-national-primary-drinking-water-regulation-lead-and-copper

|

| Environmental Protection Agency |

Priority Rec.

The Assistant Administrator for Water of EPA's Office of Water should require states to report all 90th percentile sample results for small water systems to EPA's SDWIS/Fed (or a future redesign such as SDWIS Prime) database, in its upcoming revision of the LCR. (Recommendation 2) |

On January 15, 2021, EPA issued a final regulation revising the Lead and Copper Rule that, once in effect, would implement this recommendation. The final rule would require states to report to EPA all 90th percentile lead levels for all size public water systems. The rule doesn't specify how such reporting will occur but EPA officials told us that reporting will be done through SDWIS and that EPA is developing a state module for SDWIS for states to use to oversee implementation of the final rule. We closed this recommendation as implemented after the rule went into effect on December 16, 2021. For more information, see EPA's website: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/review-national-primary-drinking-water-regulation-lead-and-copper

|

| Environmental Protection Agency |

Priority Rec.

The Assistant Administrator for Water of EPA's Office of Water and the Assistant Administrator of EPA's Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance should develop a statistical analysis that incorporates multiple factors--including those currently in SDWIS/Fed and others such as the presence of lead pipes and the use of corrosion control--to identify water systems that might pose a higher likelihood for violating the LCR once complete violations data are obtained, such as through SDWIS Prime. (Recommendation 3) |

EPA agreed with our recommendation. In April 2023, the agency proposed revisions to the Consumer Confidence Report Rule and in May 2024 EPA finalized the rule. The final rule requires states and others with primary enforcement authority to annually report drinking water compliance monitoring data to EPA, starting in May 2027. We think this is a good step forward, and we will monitor EPA's efforts to demonstrate plans for using the improved compliance monitoring data, including developing the statistical analysis we recommended. By fully implementing our recommendation, EPA will be better able to target its oversight of water systems.

|